The Importance of Fighting the Arms

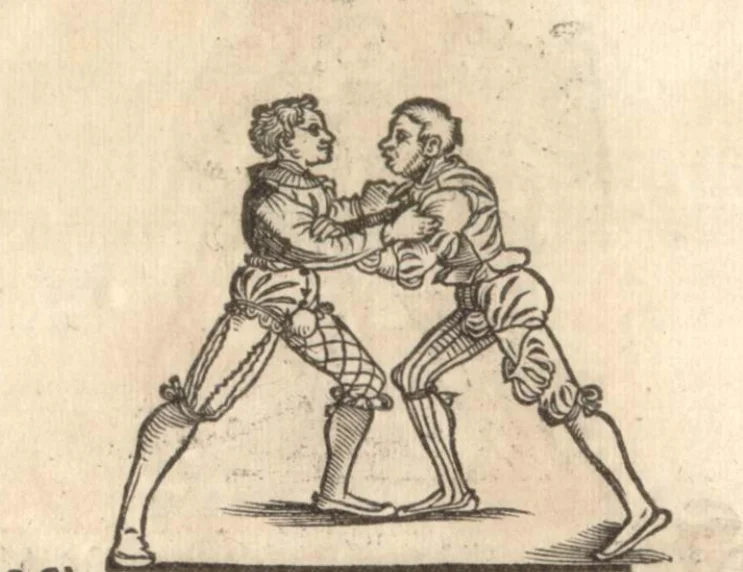

Der Altenn Fechter anfengliche Kunst, printed by Christian Egenolff. Courtesy of wiktenauer.com

I think it’s safe to assume that the demographic for my blog consists mainly of Jiu-jitsu practitioners and practitioners of the Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA). I’m going to try to make this explicable to both camps, which means it may read like a history lesson some times, but what I hope people get out of this is a sense of how medieval people wrestled and how the lessons their coaches taught may still be relevant to modern martial arts.

Many of the early manuals in the German wrestling tradition describe a common rule set in which wrestling matches began from specific grips at the arms, but wrestlers were free to change grips during the course of a match. There are numerous grappling sports that include either fixed grips, or a proscribed starting position, but I believe German Ringen (wrestling) is a special case. Ringen wasn’t simply a popular sport; it was an integral part of the training of knights and soldiers. One fencing master famously said “Alles fechten kommt aus ringen” (all fighting comes from wrestling). That’s one of my favorite quotes.

I believe it’s worth examining the rules and techniques of sportive Ringen in order to gain insight into the nature of medieval unarmed combatives, both for the sake of historical insight and, on the off chance that medieval wrestling has some insights to offer modern martial artists. So, what can be learned about the strategies of medieval wrestling from the starting grips?

First, the fact that sportive wrestling began from fixed grips means that wrestlers weren’t practicing much of the hand fighting common to modern grappling styles. If you watch modern wrestling or Judo, you will see that a lot of a bout is spent playing a kind of combative pat-a-cake as each competitor attempts to bypass the other’s hands in order to find grips at the arms/legs/head/body. In Mixed Martial Arts, that sort of hand fighting is far less prevalent, although not entirely absent, as fighters tend to achieve attachment by crashing past their opponent’s defenses with a series of blows or slipping past their opponent’s hands as the hands are extended to strike.

In the medieval context, blows were an even bigger game changer because, on the battlefield, closing to wrestle meant circumventing an enemy’s weapon, not his empty hands. It’s not surprising that the wrestling instructors of the time skipped over hand fighting to get to what they felt would be essential in a real fight, and left the practice of entering into the wrestle as the purview of weapons training.

For me, that adequately explains why German wrestling began from grips, but not why the specific grips at the arms were favored. Was there something tactically advantageous about those grips, or were they particularly useful teaching tools for medieval coaches trying to impart certain principles?

When gripping a person by the arms, the primary point of control is the elbow. Where elbow control excels is in creating empty space by flaring an opponent’s arm, off balancing an opponent by sagging their elbow away from their center of gravity, or setting up transitions to arm drags or the 2-on-1 position. Those three strategies are prominently featured in the writings of the influential German wrestling master Ott Jud.

In particular, the first technique Ott describes is a fireman’s carry when an opponent’s lead arm is high. The second technique is an outside trip when the opponent’s lead arm is low. This principle of attacking where your opponent isn’t shows up in several places in Ott’s writing and reminds me of the concept of “lazy” Jiu-jitsu. Ott’s material on wrestling at the arms teaches how to avoid fighting strength with strength and instead see how an opponent’s movements offer gifts of opportunity. As a coach, I think that’s exciting and I talk about that principle in the arm fight a lot, but I don’t think it’s THE reason the Germans wrestled at the arms.

Reviewing Ott with Drei Wunder WMA at Nemesis Jiu-jitsu. Please note: performing the fireman's throw from the knees is a modern adaptation.

As I said earlier, Ringen was meant as training in preparation for fights that could include everything from bare knuckles, to daggers, to messers (the medieval equivalent of machetes), to longswords or spears. What makes wrestling at the arms an important training tool for that context is that controlling the arms also serves to control the weapons in a way that wrestling at the body doesn’t. The postures Ott and his contemporaries advocate do more than set up wrestling techniques; they can be used to stifle attempts to punch or kick.

Someone who has been training Ott’s fireman’s carry can feel an attempted hook to their head as a feed to aid their wrestling. The prevalence of the 2-on-1 in Ringen means that practitioners on a battlefield would intuitively know how to seize the arm of a sword wielding opponent. Perhaps most importantly, anyone trying to draw a weapon while wrestling at the arms violates key principles of defensive wrestling posture and that turns the enemy’s threat of deploying a weapon into an opportunity to take them down.

There are modern accounts of people who thought they were participating in an unarmed brawl only to discover that, while they were attempting to box or wrestle, their opponent had drawn a knife and proceeded to stab them. This is a terrifying possibility, and one that the arm grips of medieval Ringen neatly minimizes. If you fight someone by grasping their dominant hand inside the elbow, it’s quite difficult for them to hit you with that hand, but more than that, it’s possible for you to feel if they reach for a weapon and preempt their draw. I tell my students if they’re ever in a fight with someone who’s more interested in reaching toward their own pockets than throwing a punch, that person is probably trying to draw a weapon (I also tell my students that getting into fights is dumb, largely avoidable and, if they want to get beat up, they should just come into the gym more often).

Nothing fancy, and both these guys were exhausted by this point in the day, but notice how little Spencer is being horribly stabbed.

To my mind, the great strength of Ringen is not simply that the techniques teach principles that are applicable to an armed fight, it’s that the strategies don’t have to adapt depending on the fight. In sportive Ringen, students are taught to sag on an opponent’s arm to set up a trip. If, having grasped someone in a fight, the opponent reaches to draw a knife from their back, it’s not necessary for the wrestler to know there’s a knife. They should simply respond to the postural invitation and trip their opponent to the ground while retaining control of that dominant arm. No extra awareness or tactical considerations required. What worked in the sport context should work the same in self-defense.

So, the fact that the sport teaches functional self-defense techniques is great, but the fact that those techniques can be applied without requiring significant mental adjustments on the part of the practitioner is awesome. Students who come to me to learn self-defense don’t need to know about the realities of the Medieval German battlefield, but they can benefit from learning fight strategies that work against fists and knives alike and don’t require them to think too much under duress. Likewise, many of my Jiu-jitsu students are more concerned with sport than self-defense, but I can tell them that concentrating on arm control the 2-on-1 is a viable strategy in the sport with the added benefit of functioning, largely unmodified, in self-defense.